Submitted by Denair Unified School District

Taking over six math classes a month into the school year isn’t the preferred way for a new teacher to join a staff. But Russ Hess didn’t have a choice. He didn’t become aware that Denair High School was looking for a teacher until well after classes began last August 12. And by the time he went through the interview process and was hired, a long-term substitute had been in place for four weeks. Hess may have gotten a late start, but he’s worked hard to make up for it.

“It was difficult because – no fault to the sub – (the classroom environment) was so loose and I’m very strict,” said Hess. “I didn’t have time to prep. I haven’t had time to get my room in shape.”

There was a bigger issue: Hess also didn’t have a California teaching credential, though he had spent the previous five years teaching math and science at Brethren Heritage School, a private campus in Salida. He worked with the Stanislaus County of Office of Education to gain recognition of his proficiency based on his classroom experience and a double math major from Central Washington University.

Despite those initial hurdles, Hess quickly made a positive impression.

“One of his strengths is that Mr. Hess expects mastery,” said Christine Skinner, Denair’s associate director of secondary education. “He gives frequent concept mastery quizzes that students have to pass or retake until they do.”

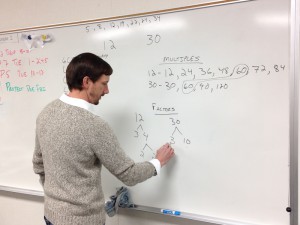

Hess teaches three periods each of algebra and geometry, classes filled mostly with freshmen and sophomores. He recognizes that making math’s abstract ideas seem relevant to them can be difficult.

“I dream about math sometimes and wake up with ideas,” he admitted.

One of those middle-of-the-night thoughts dealt with “nets,” which are two-dimensional paper diagrams with cuts and folds used to create three-dimensional figures such as cubes, cylinders, cones, prisms and pyramids. Hess came up with a team project for his geometry students that required them to build a three-dimensional town using a variety of shapes.

Team grades were based upon the brainstormed design concept, the use of the required shapes, the execution and explanation, and a group report. The completed projects can be seen on shelves and countertops all around his classroom.

“It’s really important because you can memorize things, but until you take these shapes and understand how the nets work, you don’t really get it,” Hess explained.

For his algebra classes, he assigned a project about the relationship between fuel consumption and value in cars. Students again were divided into small teams. They had to use multiple charts to compare five vehicles of their choosing to determine how many years it would take an expensive high-mileage car to have an overall cost the same as a cheaper low-mileage vehicle based on initial investment, the price of gas and miles driven.

“It takes inequalities and gets them thinking,” Hess said. “You can buy a super expensive gas efficient car and it takes 20 years to pay off. It may make more sense to buy a cheaper car.”

Aligning students into preassigned teams is done on purpose.

“In life, they’ll be working in groups in almost everything they do,” he said.

Skinner said she appreciates that Hess gives students opportunities to learn math concepts, visualize the math concretely and then apply it to real-world situations.

“One day, he passed out strips of paper, tape and scissors and showed his students how to do a quick activity that demonstrated geometric planes and edges,” she said. “He comes up with projects, like the geometric city and the virtual kitchen remodel, that allow students to apply the math concepts they are studying in very real activities. Plus, he is in his room at lunch and after school to help students whenever they need it.”

Hess, who grew up in western Pennsylvania, comes from a family of carpenters, which may partially explain his fascination with angles and planes. He moved to Tuolumne County in 2002 as a 20-year-old and worked as a carpenter and cabinet maker while attending Columbia College.

He transferred to Central Washington as a math major. Working as a tutor there for other college students convinced him that “I wanted to be a teacher.”

His high school graduation class was 30 students in Pennsylvania, so Denair’s culture fits him well.

“I really like the small schools,” he said.

Despite his late start this year, Skinner said Hess has been a valuable addition to the Denair High staff.

“Many students don’t understand why they need to study math or what it has to do with their world,” she said. “Mr. Hess is helping students regain their confidence in (and hopefully appreciation for) the subject.”

Freddie Lindquist liked this on Facebook.

Debbie Cole Haile liked this on Facebook.